Oracle’s cloud may be been in the running to be the host of a massive AI training system for Elon Musk’s xAI startup, with a purported $10 billion in rentals at stake. But what is clear from Oracle’s latest financials is that the company never needed the xAI deal at all.

So when the that deal went sour and Dell and Supermicro were tapped to build the “Colossus” cluster that ended up on premises in an old Electrolux vacuum cleaner factory outside of Memphis, Tennessee, Larry Ellison just shrugged it off.

And only six months later, Ellison was at the White House along with OpenAI co-founder and chief executive officer, Sam Altman, and Masayoshi Son, founder and chief executive officer of SoftBank, which is some of the moneybags behind Altman’s Stargate Project to spend $500 billion over the next four years to advance the state of the art in AI training hardware. (The United Arab Emirates, which have $1.4 trillion in invest in various funds to diversify their country outside of the oil industry, are very likely ponying up most of the dough. Arm, Microsoft, Nvidia, Oracle, and OpenAI are the “key initial technology partners” as the announcement put it, and we see this week that CoreWeave has been added to the Stargate partner fold.

To us, it looks like Oracle and CoreWeave, and possibly Microsoft, will be hosting some of the Stargate systems. But as we said above, Oracle seems to be doing just fine with its Oracle Cloud Infrastructure cloud business without either xAI or OpenAI, which are bitter rivals.

None of that matters. What does matter – and it matters very much, as it turns out – is that an AI model can be trained anywhere, but to be useful, it has to be trained on and have access to your own corporate data. Which, for 400,000 enterprises worldwide, are stored in Oracle databases or Oracle ERP applications (which may or may not use Oracle databases). Nvidia has made a fortune off of dozens of very large customers. Knowing Larry Ellison, Oracle’s co-founder, chairman, and chief technology officer, as we do, Oracle is going to make its next large fortune – perhaps rivaling Nvidia in the longest of runs – selling GPU compute services and AI hooks into those applications and databases. The Oracle 23ai database already speaks native vector data formats and can RAG with the best of them with your corporate info.

This is where the $7.4 billion acquisition of Sun Microsystems back in 2010 – wasn’t that a long time ago? – was prophetic. Somewhere between in late 2008 and early 2009, Ellison got hardware religion and beat out IBM to acquiring the innovative but then-struggling maker of superb Unix systems that were the backbone of the early commercial Internet. And since that time the company has launched thirteen generations of Exadata database machines, which are essentially database supercomputers. (The latest, the Exadata X11M, debuted in January of this year.)

It was this experience with hardware and software co-design as well as that vast installed base of enterprises and government, academic, and research institutions that gives Oracle a very good chance to build a very big cloud business, just like the vast base of Windows Server users and the popularity of its SQL Server database and other systems software made Microsoft from a wannabe to Number Two Cloud in less than a decade.

Not for nothing – and this being Ellison, certainly not for nothing – Oracle has another advantage. It’s database is so entrenched at organizations that its largest customers do not want AWS, Microsoft, or Google running Oracle databases on their homegrown hyperscale iron. They want to run Oracle databases, and then applications, on Oracle engineered systems that are inside of the AWS, Microsoft, and Google clouds. And starting last year, this is precisely what those three big clouds did despite the fact that they do not like hardware they did not design themselves. With OCI giving customers that option, they had two choices: Do it Larry’s way, or lose the business to Larry. They chose the former, which will allow Oracle to keep its monopoly on high-end relational databases for enterprises.

Oracle has one more advantage when it comes to cloud: It is happy to make you your own personal region if you want that. No fuss, no muss. No: Well, it is almost the same as what we have in our cloud. What Oracle puts in its cloud is exactly what you put on premises, so the boundaries of who is managing what and where the gear is located is flexible. The company is happy to bill you for services rendered, and to manage the infrastructure itself based on the management telemetry of countless other customers. This is one of the hallmarks of Sun’s engineered systems, and it persists to this day.

Painting Clouds By The Numbers

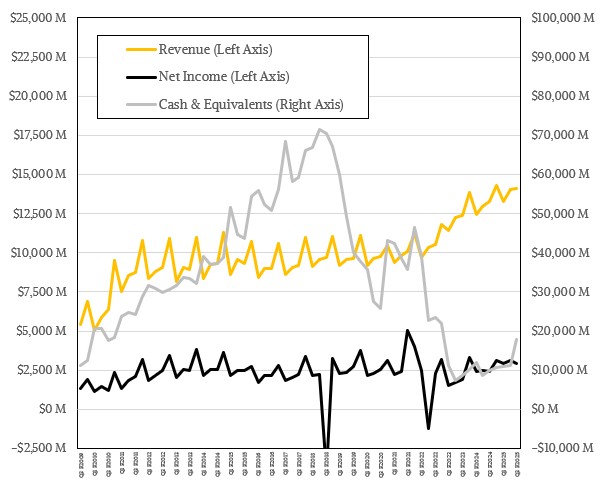

In the quarter ended in February, Oracle posted $14.13 billion in sales, up 6.4 percent year on year and just a tad bit above flat sequentially. (This was the company’s third quarter of fiscal 2025.) Net income rose much faster, increasing 22.3 percent to $2.94 billion, which works out to 20.8 percent of revenues. This is pretty good for a software maker that now has some pretty large infrastructure manufacturing costs, but it is on the low end of the average rate of profitability since the Great Recession, which is where we did a reset and started counting from. (You could argue that March 2020, the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic, was another reset point, as was the Dot-Com boon that started in 1995 and ended in the Dot-Com Bust in early 2000.)

Oracle’s cash hoard kept rising and rising even as the business kept plugging along in the 2010s. The big hit came when it repatriated overseas profits and paid taxes on it, as many tech titans did at the time. And then, Oracle used cash to aggressively buy back shares, which had the effect of boosting earnings per share, while it made some acquisitions and started to build a cloud business from scratch.

To be specific: Oracle did not blow its cash hoard building a cloud. It has been conservative and thoughtful in its rollout, and it builds when customers commit. Right now, GPU demand is much larger than supply and even Oracle wishes it could build out AI training and inference infrastructure faster. It builds at the speed it can, pairing customers with what it can get its hands on. Which is why the company’s capital expenses are, by the standards of hyperscalers and the big cloud builders, fairly modest:

Oracle spent just a smidgen under $8.7 billion on capital expenses in fiscal 2023 ended in May of that year, and fell by 21 percent to $6.87 billion in fiscal 2024. For this 2025 fiscal year, spending is expected to be about $16 billion, as Safra Catz, chief executive officer at the company, explained on a call with Wall Street analysts going over the quarter.

Oracle is on track to book $57.4 billion in revenues this year if all goes as expected, and Catz added that Oracle expects to grow by around 15 percent in fiscal 2026 to around $66 billion and raised its guidance for growth in fiscal 2027 for 20 percent growth, which works out to just shy of $80 billion. So by fiscal 2028 or so, depending on how aggressive the Stargate Project of OpenAI and SoftBank is and how much of the hosting pie Oracle gets for the Stargate systems, Oracle could be the fifth company in IT history to break $100 billion in sales into the datacenters of the world. (IBM, Hewlett Packard, Dell, and Nvidia are the other four.)

It certainly looks like Oracle is on track to do that. Without any Stargate bookings whatsoever, Oracle now has $130 billion in remaining purchase obligations, or RPOs, which is money that a service vendor has on the books. That is up 62.5 percent from Q3 F2024 and up 34 percent sequentially from Q2 F2025.

We are not going to spend a lot of time drilling into the ins and outs of the Oracle application, database, and middleware software businesses. This is a huge business and among the largest enterprise customer bases in the world that actually spend big bucks. This is the foundation on which Oracle’s AI business will be built, and in fact, as Ellison put it on the call, eventually Oracle’s applications will just be a collection of agents – we would say that this will be added to some legacy transaction processing application that do not need to be changed.

Some interesting things to call out for the fans of Sun Microsystems and Oracle engineered systems. Oracle doesn’t sell a huge amount of hardware, and this business is trending down as customer move to OCI, but it still sold nearly $3 billion in hardware in the trailing twelve months. In Q3 F2025, Oracle pushed $703 million in iron, down 6.8 percent, and we calculate that Oracle had operating income of $506 million on this iron, which is 72 percent of revenue. Which is not too shabby. Those margins are as good as Oracle is getting on cloud services, as you can see in the table below:

Oracle describes its quarterly results in two different ways. The first is by product divisions: Cloud Services, License Support, Cloud License and On Premise License, Hardware, and Services. It also talks about them by product groups: Applications Cloud Services and License Support and Infrastructure Cloud Services and License Support, which is another way to break cloud and license but by where they are vertically in the IT stack.

The point is this: Oracle’s infrastructure software business – operating systems are bundled with the hardware and so are not part of this segment – is now growing faster than its application software business on its cloud (or for software sold to run on other clouds). In the quarter, the application part of the cloud business (Oracle Fusion and NetSuite application suites and their predecessors) brought in $4.81 billion in Q3 F2025, up 5 percent. But the infrastructure cloud business grew by 15.2 percent to just a tad under $6.2 billion. Infrastructure is growing five times faster sequentially as applications. And we see no reason why this trend will not persist for a while as companies go to OCI to do the AI processing they cannot hope to easily build because they do not have the skills or the GPUs. AI will pull customers out of their on premises datacenters and onto an Oracle cloud region – even if it is a personal one among the Global 5,000 or 10,000.

Oracle mixes cloud and license revenues in its financial presentations, which we have consolidated and tweaked to get operating income in the table above. But when it talks in the statements it puts out with the numbers, it gives a set of pure revenue figures for true cloud IaaS capacity and SaaS capacity sold. Here is what it looks like:

This way of talking about the business is only a few years old, and we estimated the breakdown of Cloud IaaS versus Cloud SaaS for fiscal 2021 based on trends from fiscal 2022 to the present. A bit more than 80 percent of the pure cloud revenues at Oracle was for SaaS in fiscal 2021, but IaaS has been growing steadily as Oracle builds out the OCI cloud. IaaS has grown from under 20 percent to more than 40 percent of revenues from August 2020 to today. Oracle is interesting in that it is a SaaS vendor building an IaaS cloud, whereas Amazon Web Services was an IaaS that had to build a SaaS stack and partner with others to build that up to more than half of the business. (Microsoft was more like Oracle, for both datacenter and desktop applications, and started a decade earlier to build Azure.)

It will not be long before IaaS will be bigger than SaaS, but if GPU capacity constraints abate and supply can balance demand, prices for GPU capacity should moderate and SaaS should retake the lead from IaaS. But, then again, GenAI is doing the work of programmers, analysts, and knowledge workers, so maybe it won’t. . . .

On the call with Wall Street, Ellison said that Oracle was building a cluster based on Nvidia GB200 compute engines – that’s two “Blackwell” B200s coupled to one “Grace” CG100 processor – and having a total of 64,000 GPUs. He added that Oracle signed a multi-billion dollar contract with AMD in Q3 to build a cluster with 30,000 Instinct MI355X GPU accelerators. As we reported back in February, AMD is moving the launch of the MI355X up to the middle of the year; it was previously set for sometime in the second half of 2025. It is designed to compete with Nvidia’s “Blackwell Ultra” B300 accelerators, about which we expect to hear more next week at the 2025 GPU Technical Conference in San Jose.