Photo: Intelligencer, Photo: Read.ai

If you have a job that involves spending a lot of time in apps like Zoom, and if you work at a company that likes to experiment on its workforce with new software features, you’ve probably gotten a few notifications about exciting new developments in meetings. Microsoft Teams user? You might be getting pinged about searchable, AI-generated meeting recaps. Part of a Google workplace? Maybe you’ve been told you can ask a chatbot to take notes for you. And if you’re the sort of person whose calendar is loaded with overlapping Zoom calls, there’s a chance you’ve heard about, or used, the company’s “AI Companion” features, which include summarized transcripts, a chat interface for getting caught up, and automatic video highlights. Perhaps you haven’t run into any of these features yet, but there’s a good chance you soon will. In the last few years, LLM-based AI technology has made it trivially easy to add transcription, summarization, and analysis tools to meetings platforms.

These features exist largely because, rather suddenly, they can. Automatic transcription, in many cases powered by a specific OpenAI API, is rapidly getting better and more affordable. It’s more of a “Why not?” than a “Why?” for companies like Zoom and Microsoft, but the appeal of these features is obvious enough: Wouldn’t it be nice if you didn’t have to take notes during meetings? If you could quickly review meetings you missed? If you could go back and check what other people said, or what you said, in a meeting that was productive, intense, boring, or that went off the rails? That’s the pitch, anyway.

Use these tools for a little while, however, and they reveal themselves to be more than just obvious little feature upgrades. AI is being used here to turn meetings into content — to automatically convert meetings into a browsable, searchable, remixable form of media. In some cases, this can be funny and deflating. That meeting really could have been an email, and hey, look at that, here’s an AI summary in email form: Delay announced, project discussed, conclusions not reached, plans to meet again in a week. In others, the ability to search and chat with transcripts, particularly for meetings you missed, is simply and powerfully helpful. Will this sort of stuff make workers more productive and efficient? Maybe! It may also be the case that tools like this help to create the impression that meetings — a large majority of which, according to surveyed workers, hold employees back from what they see as their actual work — are, themselves, the job. All this AI-generated media may have some utility, but it doubles as evidence of work. You weren’t just sitting in meetings all day, you were participating in the production of content, information, and resources for the greater good of the firm! Slick, formalized, AI-generated representations of what was accomplished, or at least discussed, in meetings create the impression of productivity, or perhaps they constitute a strange mutant form of productivity in and of themselves.

Photo: Read.ai

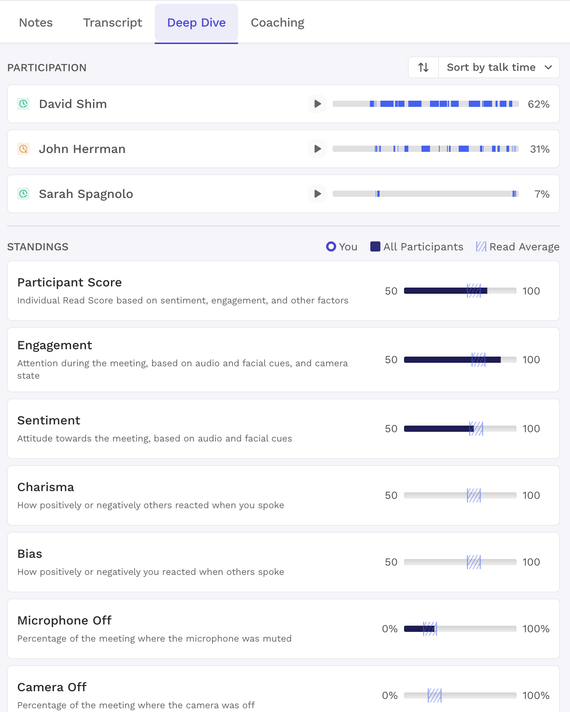

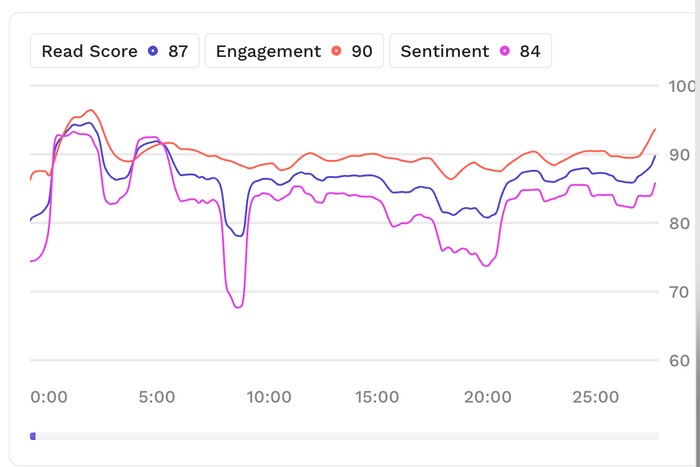

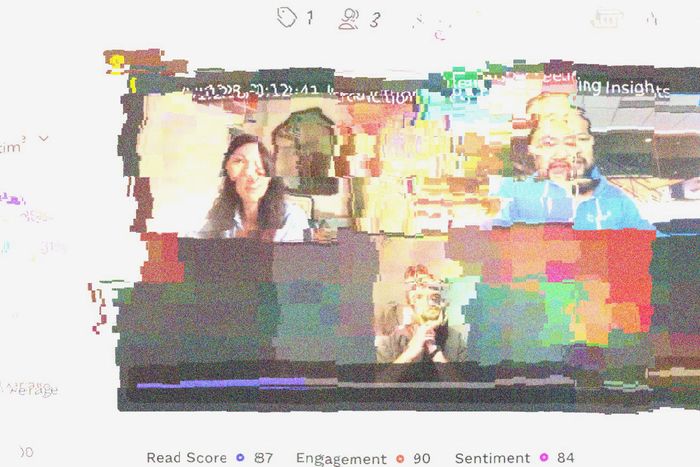

Another thing about turning meetings into replayable, analyzable, chattable content — about recording and then processing them for later consumption — is that new metrics can’t be far behind. And while companies like Microsoft and Google will be a little more cautious about meeting quantification, a crop of startups is betting on it. During a recent meeting with Read.ai, an AI assistant tool that can record and analyze meetings across different platforms by joining as a guest, the company shared with me a live analytics dashboard for the meeting we were in at that moment. One panel contained a real-time transcription of what we were saying; another informed me that I had been late, while the other two attendees had been on time; as I spoke, I watched my “Engagement” metric rise, my words-per-minute spike, and a “Sentiment” metric dip, then rise, then dip again. At the conclusion of the meeting, I could revisit not just its contents but an assessment of my performance in multiple dimensions: How much did I get to talk relative to others? Did I use too many filler words?

Photo: Read.ai

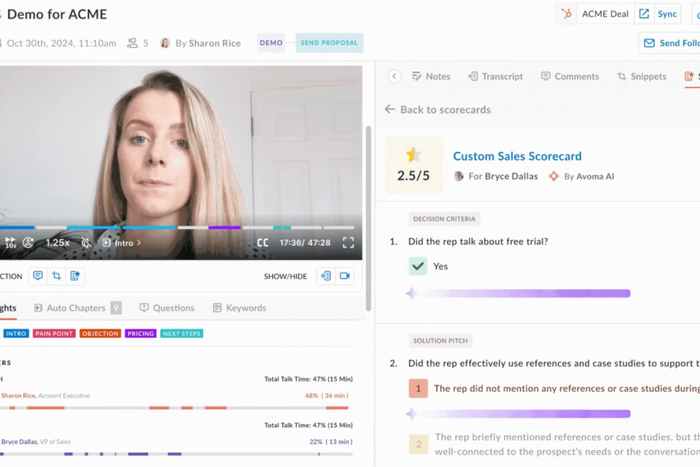

Read.ai is one of the bigger startups in this space and has ambitions beyond meetings — it pitches itself as a platform that can ingest and analyze a much wider range of data, including meetings. Other companies, however, are converging on similar concepts. There’s Avoma, which, like Read.ai, offers “coaching” based on meeting performance:

Photo: Avoma

There’s even an app called Equal Time, which pitches the time-per-speaker metric into a sort of metric for inclusion:

Photo: Equal Time

From the perspective of a meeting participant, at first glance, metrics like this are more interesting than useful. It might be good to know that you’re taking up too much space in a virtual room or that you’re barely speaking up; while contrived sentiment tools might be unreliable or opaque, maybe steep drops whenever you talk are, to you, actionable information. To me, the real-time meetings dashboard felt familiar in two ways. It was faintly reminiscent of traffic-tracking services like Chartbeat, of course, with which the online publishing industry has had a complicated and arguably counterproductive relationship for well over a decade (but which remain in wide use). But it most reminded me of the adrenal sensation of going live on a streaming platform like Twitch or TikTok, where your performance is influenced in real time by numbers that change as the stream goes on.

As fun and/or depressing as it might be to entertain the possibility of metrics-driven meetings-as-content — of a world in which office workers are gradually incentivized to become intra-office content creators trying to build audiences, where endlessly circling back and touching base becomes a quantified goal unto itself, and where the post-Zoom, post-Slack performance of work fully becomes the work — these are primarily enterprise tools, designed with corporate licenses and the needs of management in mind. From the perspective of people who oversee meetings, rather than merely joining them, these metrics have other obvious uses. They quantify comparative participation. They keep a log of who shows up and, in some cases, who is paying attention. They attempt to assess how meetings are going and how individuals are performing within them with measures derived from imperfect, opaque, but plausible-seeming machine analysis. They’re more than just metrics, in other words, or digests and summaries created to help keep participants organized. They’re a form of surveillance.

The near future of video meetings offers a strange and complicating preview of how AI-based technology might infiltrate the office, the way it has, in previous forms, factories and call centers. On one hand, everyone has a note-taking assistant with an aptitude for crunching numbers and keeping track of large amounts of boring or unnecessarily obscure information. But this assistant reports directly to management, tracks your performance, and constantly nudges you to behave and perform in specific ways according to the preferences on which it was trained or toward which it is explicitly guided. In the AI-driven office of the future, everyone gets a robot intern. The bad news is that the robot intern is also your boss.